Once a baby is brought into the world, either naturally or through adoption, there are so many changes and shifts in the family as a whole, and in individual roles and expectations. What most people don’t consider is that depression and anxiety happens even after a child is added to the family through adoption. In order to get a clear grasp on the “why” it occurs even without the hormonal changes, we have to define the “what.”

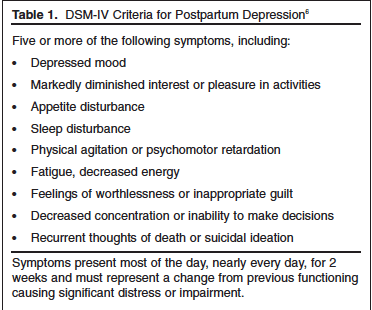

Postpartum depression symptoms frequently includes the following:

Postpartum Anxiety (although not as frequently diagnosed or sought help for but is likely just as common), includes:

-

Dread or a sense of danger

-

Racing thoughts

-

A persistent feeling of being on edge, like something is about to go terribly wrong

-

Excessive worry about the baby’s health, development or safety

-

An overwhelming sense of burden, stress and concern about the ability to be a good parent

-

A persistent case of the jitters or a constant agitated feeling

-

Insomnia or trouble falling or staying asleep

-

Changes in heart rate and breathing, including elevated heartbeat, rapid breathing and/or chest pain, especially if the anxiety takes the form of panic attacks

In adoption, we don’t know the national statistics on how prevalent PPD/PPA. All we know is that the subject is lacking research and reveals repeatedly how high the need is for support and normalization of feeling these things. After all, if women who birth and raise their children are at a 10-15% likelihood for developing PPD (Vigod, Simone N., et al., 2010), (and some studies indicate by state the numbers could be more like 1 in 5 of women), we can estimate that the numbers for adoptive families are near that as well, since hormonal changes have not been determined the causal contributor for this diagnosis (Vigod, Simone N., et al., 2010).

Families who adopt have many factors out of their control. Prenatal care and the child’s delivery and/or care at the place of birth is the choice of the first mama. But these factors that are out of the adoptive parent’s control can increase anxiety about the child’s quality of care and their roles postpartum. This sense of feeling out of control or powerless over decisions that were made for the child’s prenatal and postnatal care can increase the likelihood that parents struggle with anxiety once baby is home. Further, adoptive parents may struggle to bond or feel feelings of fondness for the infant for the first few months of the child’s life. Simply because this is adoption, it can add to the guilt of the birth mother’s loss, or a sense of inadequacy on the part of the parent’s. There are simply too many “whys” for why a parent could struggle with PPD/PPA after bringing home their baby after adoption. Many sources indicate exhaustion and interrupted sleep cycles for feelings of depression/anxiety. There is plenty of data correlating the demands of caring for an infant (Cooper et al. 2007) with higher rates of depression and anxiety…and this can particularly impact parents with kiddos facing time in the NICU. Higher needs babies can elevate parent’s cortisol and stress levels. When there is withdrawal and substance exposure in addition to many of the already mentioned factors, it is to be expected that on some level that new parents will be feeling human: vulnerable, exhausted and overwhelmed.

We can’t overlook the impact of infertility either. Just because a baby has finally been brought home, the feelings of loss related to infertility can peak around this time in some instances. As humans, we were created to hold the tension of conflicting feelings. Joy and loss. Gratitude and grief. Hope and disappointment. These feelings are normal and somewhat to be expected in the complicated nature of adoption.

Treating PPD/PPA

Interestingly, treating depression and anxiety in adoptive parents are the same for that of birth parents. Research has shown several types of psychotherapy to be the most effective in providing positive outcomes: individual interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy and group/family therapy (Perfetti, Clark & Fillmore, 2004). Mother-infant therapy groups can be another source of relief for mothers facing these feelings. Adoptive families need the same kind of treatment a biological family needs postpartum: meals, help with other children or chores, AND SUPPORT.

“medications result in relatively poorer compliance than psychotherapy, have a higher dropout rates, and result in as much as a 60% non-response rate with some patient populations. Psychotherapy can teach skills to help prevent depression, making such treatment an attractive, cost-effective alternative to drug treatments” (1995, pg 547).

If you are a parent right now feeling the weight of depression and anxiety after bringing home your child through adoption, please know that you are not alone and that these complicated feelings are more common than you may believe. These feelings and sensations do not make you a bad parent or a bad person. Please do not go through this alone, and know there is a way to face depression and anxiety with hope and with resources to get through this extremely difficult time.

—-

Sources

Antonuccio, David O., William G. Danton, and Garland Y. DeNelsky. “Psychotherapy versus medication for depression: challenging the conventional wisdom with data.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 26.6 (1995): 574.

Bauman BL, Ko JY, Cox S, et al. Vital Signs: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Provider Discussions About Perinatal Depression — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:575–581. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6919a2external icon.

Clark, Roseanne, Audrey Tluczek, and Amy Wenzel. “Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a preliminary report.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 73.4 (2003): 441-454.

Cooper C, Jones L, Dunn E, Forty L, Haque S, Oyebode F, Craddock N, Jones I (2007) Clinical presentation of postnatal and nonpostnatal depressive episodes. Psychol Med 37:1273–1280

Perfetti, J., Clark, R., & Fillmore, C. M. (2004). Postpartum depression: identification, screening, and treatment. WMJ-MADISON-, 103, 56-63.

Vigod, Simone N., et al. “Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low‐birth‐weight infants: a systematic review.” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 117.5 (2010): 540-550.

Zhou, Jiani et al. “Treatment of Substance Use Disorders Among Women of Reproductive Age by Depression and Anxiety Disorder Status, 2008-2014.” Journal of women’s health (2002) vol. 28,8 (2019): 1068-1076. doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.7597

——

Our guest blogger, Ashley Enderle, is a licensed associate counselor and practices at Ataraxis Counseling in North Phoenix. She specializes in treating maternal issues like PPD/PPA and all things faced in womanhood. Not only is she a mental health therapist, but she is an adoptive mom as well. Tune in to read about how you could be struggling with more than just adjusting to a new baby. To find out more about her services you can visit ataraxicounseling.com.

Once a baby is brought into the world, either naturally or through adoption, there are so many changes and shifts in the family as a whole, and in individual roles and expectations. What most people don’t consider is that depression and anxiety happens even after a child is added to the family through adoption. In order to get a clear grasp on the “why” it occurs even without the hormonal changes, we have to define the “what.”

Postpartum depression symptoms frequently includes the following:

Postpartum Anxiety (although not as frequently diagnosed or sought help for but is likely just as common), includes:

-

Dread or a sense of danger

-

Racing thoughts

-

A persistent feeling of being on edge, like something is about to go terribly wrong

-

Excessive worry about the baby’s health, development or safety

-

An overwhelming sense of burden, stress and concern about the ability to be a good parent

-

A persistent case of the jitters or a constant agitated feeling

-

Insomnia or trouble falling or staying asleep

-

Changes in heart rate and breathing, including elevated heartbeat, rapid breathing and/or chest pain, especially if the anxiety takes the form of panic attacks

In adoption, we don’t know the national statistics on how prevalent PPD/PPA. All we know is that the subject is lacking research and reveals repeatedly how high the need is for support and normalization of feeling these things. After all, if women who birth and raise their children are at a 10-15% likelihood for developing PPD (Vigod, Simone N., et al., 2010), (and some studies indicate by state the numbers could be more like 1 in 5 of women), we can estimate that the numbers for adoptive families are near that as well, since hormonal changes have not been determined the causal contributor for this diagnosis (Vigod, Simone N., et al., 2010).

Families who adopt have many factors out of their control. Prenatal care and the child’s delivery and/or care at the place of birth is the choice of the first mama. But these factors that are out of the adoptive parent’s control can increase anxiety about the child’s quality of care and their roles postpartum. This sense of feeling out of control or powerless over decisions that were made for the child’s prenatal and postnatal care can increase the likelihood that parents struggle with anxiety once baby is home. Further, adoptive parents may struggle to bond or feel feelings of fondness for the infant for the first few months of the child’s life. Simply because this is adoption, it can add to the guilt of the birth mother’s loss, or a sense of inadequacy on the part of the parent’s. There are simply too many “whys” for why a parent could struggle with PPD/PPA after bringing home their baby after adoption. Many sources indicate exhaustion and interrupted sleep cycles for feelings of depression/anxiety. There is plenty of data correlating the demands of caring for an infant (Cooper et al. 2007) with higher rates of depression and anxiety…and this can particularly impact parents with kiddos facing time in the NICU. Higher needs babies can elevate parent’s cortisol and stress levels. When there is withdrawal and substance exposure in addition to many of the already mentioned factors, it is to be expected that on some level that new parents will be feeling human: vulnerable, exhausted and overwhelmed.

We can’t overlook the impact of infertility either. Just because a baby has finally been brought home, the feelings of loss related to infertility can peak around this time in some instances. As humans, we were created to hold the tension of conflicting feelings. Joy and loss. Gratitude and grief. Hope and disappointment. These feelings are normal and somewhat to be expected in the complicated nature of adoption.

Treating PPD/PPA

Interestingly, treating depression and anxiety in adoptive parents are the same for that of birth parents. Research has shown several types of psychotherapy to be the most effective in providing positive outcomes: individual interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy and group/family therapy (Perfetti, Clark & Fillmore, 2004). Mother-infant therapy groups can be another source of relief for mothers facing these feelings. Adoptive families need the same kind of treatment a biological family needs postpartum: meals, help with other children or chores, AND SUPPORT.

“medications result in relatively poorer compliance than psychotherapy, have a higher dropout rates, and result in as much as a 60% non-response rate with some patient populations. Psychotherapy can teach skills to help prevent depression, making such treatment an attractive, cost-effective alternative to drug treatments” (1995, pg 547).

If you are a parent right now feeling the weight of depression and anxiety after bringing home your child through adoption, please know that you are not alone and that these complicated feelings are more common than you may believe. These feelings and sensations do not make you a bad parent or a bad person. Please do not go through this alone, and know there is a way to face depression and anxiety with hope and with resources to get through this extremely difficult time.

—-

Sources

Antonuccio, David O., William G. Danton, and Garland Y. DeNelsky. “Psychotherapy versus medication for depression: challenging the conventional wisdom with data.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 26.6 (1995): 574.

Bauman BL, Ko JY, Cox S, et al. Vital Signs: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Provider Discussions About Perinatal Depression — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:575–581. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6919a2external icon.

Clark, Roseanne, Audrey Tluczek, and Amy Wenzel. “Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a preliminary report.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 73.4 (2003): 441-454.

Cooper C, Jones L, Dunn E, Forty L, Haque S, Oyebode F, Craddock N, Jones I (2007) Clinical presentation of postnatal and nonpostnatal depressive episodes. Psychol Med 37:1273–1280

Perfetti, J., Clark, R., & Fillmore, C. M. (2004). Postpartum depression: identification, screening, and treatment. WMJ-MADISON-, 103, 56-63.

Vigod, Simone N., et al. “Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low‐birth‐weight infants: a systematic review.” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 117.5 (2010): 540-550.

Zhou, Jiani et al. “Treatment of Substance Use Disorders Among Women of Reproductive Age by Depression and Anxiety Disorder Status, 2008-2014.” Journal of women’s health (2002) vol. 28,8 (2019): 1068-1076. doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.7597

——

Our guest blogger, Ashley Enderle, is a licensed associate counselor and practices at Ataraxis Counseling in North Phoenix. She specializes in treating maternal issues like PPD/PPA and all things faced in womanhood. Not only is she a mental health therapist, but she is an adoptive mom as well. Tune in to read about how you could be struggling with more than just adjusting to a new baby. To find out more about her services you can visit ataraxicounseling.com.