Torie and her family

This guest blog post is written by Torie DiMartile, who runs the Instagram page Wreckage and Wonder where she shares adoption related resources, her own experience as a transracial adoptee and where she fosters conversation about faith, identity, race and parenting transracial adoptees. She’s a doctoral student studying identity construction for domestic transracial adoptees at Indiana University. She’s a poet, an artist, a lover of cinnamon rolls and pasta and antique shops. You can follow her on her page @wreckageandwonder where you can learn more about her, find resources and buy her art.

—————————————————

Last week, in national news, a white supremacist opened fire at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas. The same week, in my little university town of Bloomington IN, the farmers market endured its second week of cancelled activity due to white supremacist threats.

Torie and her mom as a child

Torie and her mom as a child

If you ask my mom, she’ll readily tell you that 26 years ago these terrifying racial headlines would have flickered across her screen with a pang of sympathy, but they would not have drastically impacted her daily life. Of course, she knew racism and violence existed, but it existed outside her own experience. Today, as the mother of a 26-year old transracial adoptee those headlines probably keep her up at night. They inspire her to read books on race and join church organized racial reconciliation workshops. They keep her in a constant mindset of education, advocacy and awareness so she can continue to be the best possible parent to her child of color navigating a world that never ceases to emphasize the dividing line between black and white.

Transracial adoption is simultaneously the most rewarding and difficult experience of my life. I have been knocked down by it and I have been built up by it. Growing up without racial mirrors within my immediate family, educational community or spiritual community is a hurt and confusion I continue to soothe even after all these years. And despite the hard work on my parent’s side and the intense love between us, there is still a fundamental difference in how we experience the world and that can lead to frustration, hurt feelings and a gap that sometimes feels impossible to bridge. However, there is a wealth of patience and empathy that those challenges have cultivated in both myself and my parents and a love that continuously seeks to be acted out in grace.

So, given the racially charged environment in which we live, the constant ebb and flow of the news cycle and the inevitability of never fully understanding what it means to live life as a person of color, how can white adoptive parents provide a safe and validating environment for their children to cultivate and express their unique racial identity? What are some things as a transracial adoptee I would want all white adoptive parents to know as they consider this journey?

1. Diversify your bookshelves. It feels like this is so obvious, but I will never stop repeating it because I believe in its enduring power to create a positive self-esteem. Your child needs to see themselves in their bedtime stories, on the TV, in the art in your office, and in your holiday decorations.

Some of my favorite memories as a child were reading All the Colors of the Earth (https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/409344.All_the_Colors_of_the_Earth) with my mom and getting to play with the African Kwanzaa figurines at Christmas time.

At 26-years old I still have some of my favorite storybooks proudly displayed on my bookshelf and still read them with love.

-

Happy to be Nappy: https://www.amazon.com/Happy-Be-Nappy-Board-Book/dp/1484788419

-

When God Made You: https://www.amazon.com/When-Made-Matthew-Paul-Turner/dp/1601429185

-

Books by Ezra Jack Keats: https://www.amazon.com/s?k=Ezra+Jack+keats&i=stripbooks&ref=nb_sb_noss_2

-

And That’s Why She’s My Momma :https://books.google.com/books/about/And_That_s_Why_She_s_My_Mama.html?id=xr6gtAEACAAJ&source=kp_cover

2. Develop meaningful relationships with people of color. Your child needs to see you developing relationships with people of color for the value of those relationships in YOUR life, not just your child’s life. People of color should be peers, mentors, confidantes that enrich your life with friendship and leadership. Your child should know by looking at your life that people of color are important. If you are hoping to adopt, I highly recommend sitting down and brainstorming ways you can begin creating a multiracial community that can be part of your life before and after you adopt. Seek out racially and ethnically diverse places of worship. Attend activities and workshops at your local library. Check out festivals and history events. If you have already adopted but do not have black or brown relationships, it’s never too late to start. Remember, people of color are not a “diverse friend” to be checked off on a list and they aren’t your personal race consultant – be sure to value the brown and black people in your life for who they are and not what they can give you.

3. Advocate for the personal and political interests of your child’s community. It’s important for your child to see you educating yourself, sticking up for black and brown people in conversation, staying up to date with the news and policy-changes that impact communities of color. Your child should see and know that their community is now your community. The willingness you have to advocate for people of color will directly translate to your willingness to advocate for your child of color.

4. Diverse community is an intentional choice not a haphazard accessory. Field trips to the Black history museum and culture campus once a year are not going to provide your child the opportunity to explore their racial identity and learn from others about what it means to be brown or black in the world. Because I did not have friends of color until college, it was an awkward, confusing and painful experience to open up to and get to know other people of color. By living in a different neighborhood, or seeking out a more diverse place of worship, I could have begun developing relationships with people of color far before I left high school, giving me the skills and confidence to continue forging those meaningful connections. Lack of engagement with black and brown people in consistent and positive ways early in your child’s life can hinder their ability to relate to and build relationships with people of color later on.

5. It’s okay not to have all the answers. In fact, you won’t have all the right answers. While every parent wants to provide the absolute best for their children, I find white adoptive parents are especially eager to fill the gaps they fear their child might experience. It’s important to realize that even if you “check” off all the so-called right boxes in terms of providing your child an environment where they can foster a positive racial identity, your child might still struggle with their racial identity. It’s more important to focus on ways your child can cope with frustration, sadness, etc. than trying to prevent them from experiencing those emotions.

Things my parents did well:

-

They incorporated my racial identity in daily life. From books, to music, to plays to household art, my parents made sure I was able to see my racial identity reflected in our home.

-

They listened. Conversations about race can be hard and messy. Sometimes feelings are hurt, and experiences are misunderstood. My mom could have easily entered into conversations about race with an arsenal of excuses, justifications and explanations. But she didn’t. She set down her defenses and did her best to simply listen.

-

They didn’t rely on me for education. While I might suggest books or articles about race my mother always went the extra mile to roll up her sleeves and do the heavy lifting herself.

-

They take my personal safety seriously. They don’t minimize the oftentimes violent situations I might encounter living in an area of the Midwest that continues to have active hate groups. They check in, stay up to date on national news, and give me an extra financial boost for buying a better parking pass or purchasing personal self-defense devices.

-

They always celebrated by racial identity. My skin, my hair, my racial history was always spoken of with love.

-

They believed me. When I would (and still do) come home with experiences of racism or prejudice they don’t question if it’s true. They don’t ask me if I did something wrong. They don’t brush it under the rug. They don’t tell me I’m over-reacting. They trust that my experiences as a woman of color in the world are real and valid.

Living as a woman of color in an oftentimes unpredictable racial climate can be scary, exhausting and discouraging and living as the parent of a transracial adoptee in such an environment can be difficult. Just as I believe I can walk this life as a woman of color with grace and intention despite the obstacles, I believe transracial adoption, though complicated, is possible. Once hopeful adoptive parents view their child’s racial identity as worthy of just as much emotional labor as other aspects of their child’s well-being, they can begin to equip their child with the necessary tools to view the difficulties of transracial adoption not as insurmountable burdens but as enriching complexities in their already beautiful life.

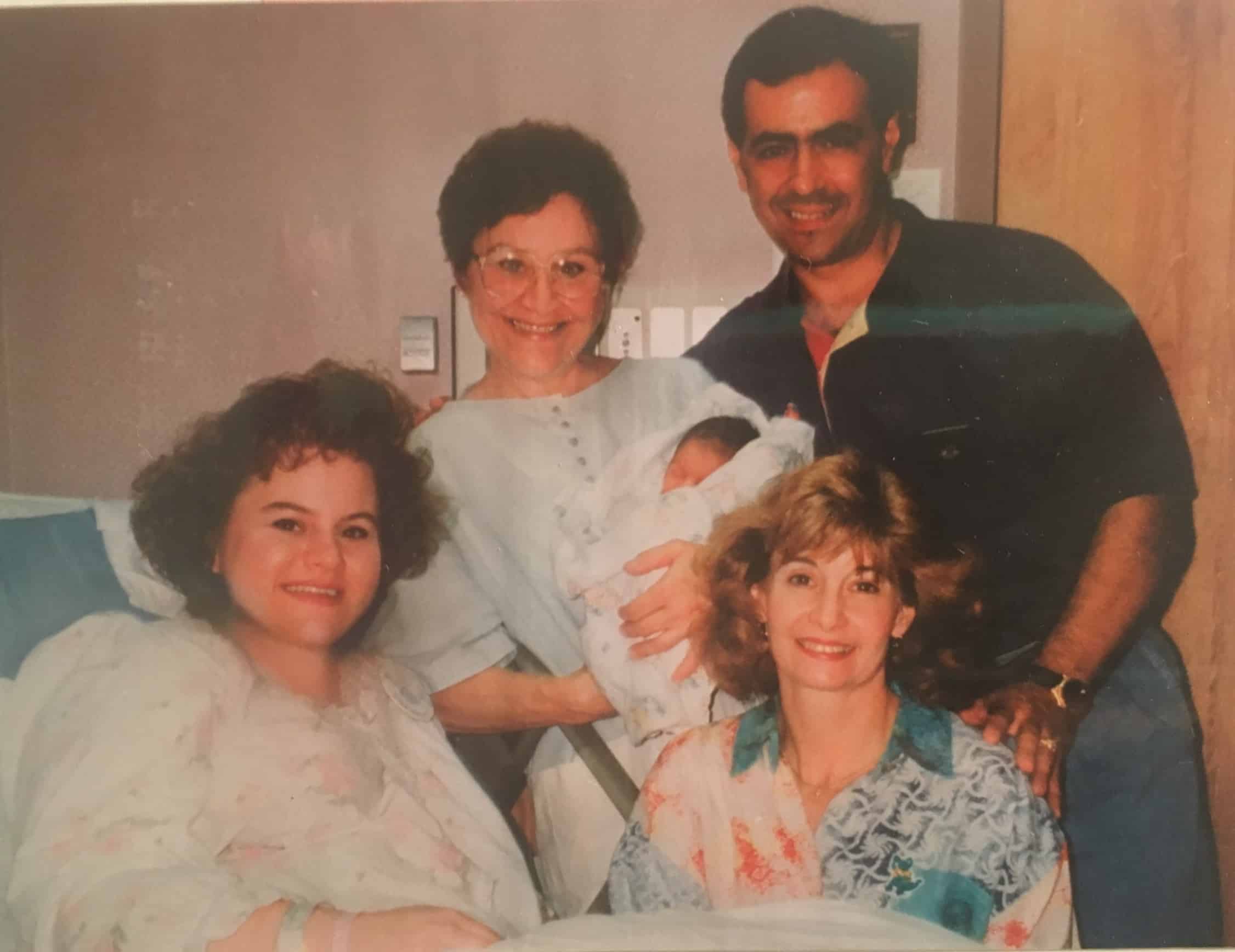

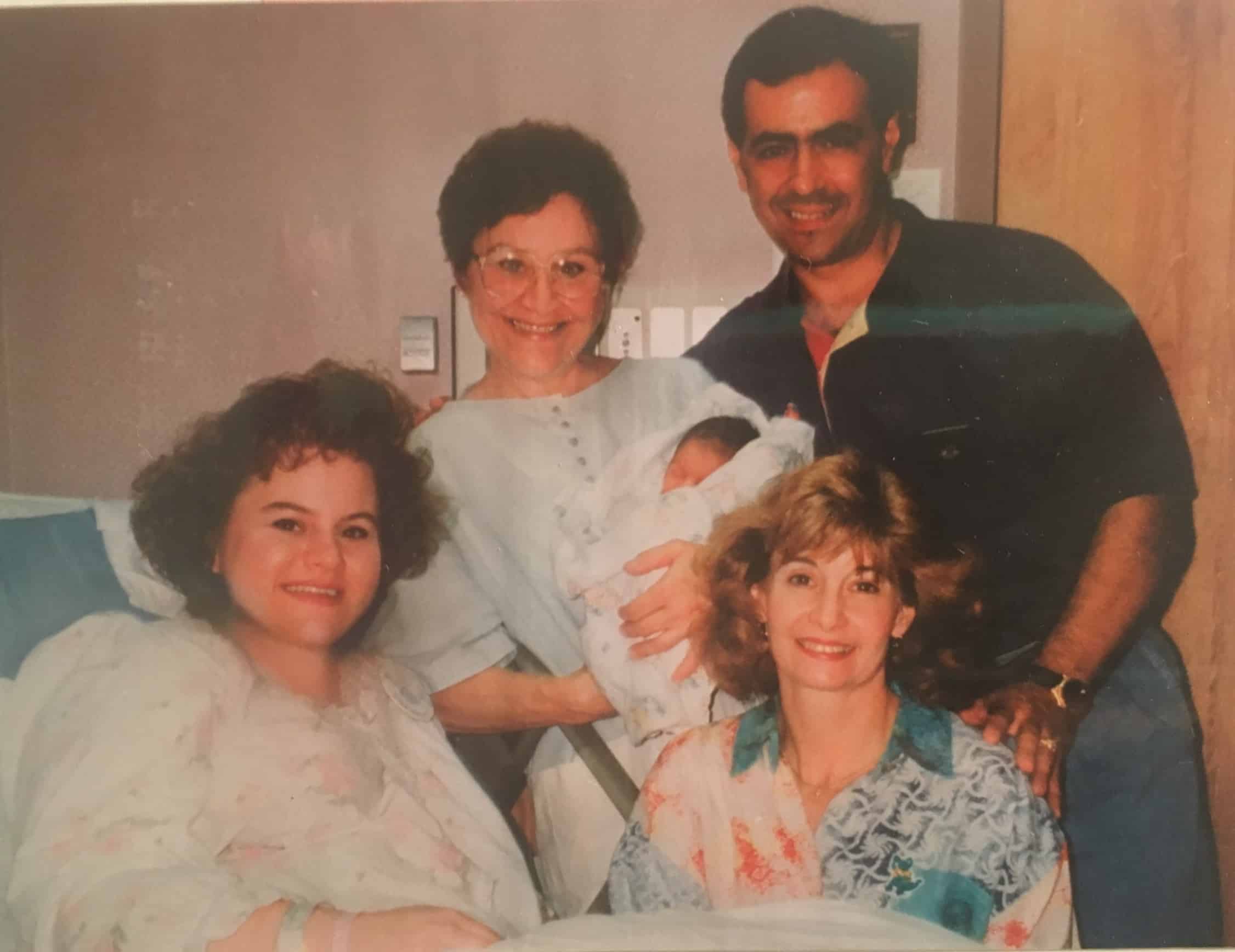

Torie and her family in the hospital after she was born

Torie and her family in the hospital after she was born

Torie and her family

This guest blog post is written by Torie DiMartile, who runs the Instagram page Wreckage and Wonder where she shares adoption related resources, her own experience as a transracial adoptee and where she fosters conversation about faith, identity, race and parenting transracial adoptees. She’s a doctoral student studying identity construction for domestic transracial adoptees at Indiana University. She’s a poet, an artist, a lover of cinnamon rolls and pasta and antique shops. You can follow her on her page @wreckageandwonder where you can learn more about her, find resources and buy her art.

—————————————————

Last week, in national news, a white supremacist opened fire at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas. The same week, in my little university town of Bloomington IN, the farmers market endured its second week of cancelled activity due to white supremacist threats.

Torie and her mom as a child

Torie and her mom as a child

If you ask my mom, she’ll readily tell you that 26 years ago these terrifying racial headlines would have flickered across her screen with a pang of sympathy, but they would not have drastically impacted her daily life. Of course, she knew racism and violence existed, but it existed outside her own experience. Today, as the mother of a 26-year old transracial adoptee those headlines probably keep her up at night. They inspire her to read books on race and join church organized racial reconciliation workshops. They keep her in a constant mindset of education, advocacy and awareness so she can continue to be the best possible parent to her child of color navigating a world that never ceases to emphasize the dividing line between black and white.

Transracial adoption is simultaneously the most rewarding and difficult experience of my life. I have been knocked down by it and I have been built up by it. Growing up without racial mirrors within my immediate family, educational community or spiritual community is a hurt and confusion I continue to soothe even after all these years. And despite the hard work on my parent’s side and the intense love between us, there is still a fundamental difference in how we experience the world and that can lead to frustration, hurt feelings and a gap that sometimes feels impossible to bridge. However, there is a wealth of patience and empathy that those challenges have cultivated in both myself and my parents and a love that continuously seeks to be acted out in grace.

So, given the racially charged environment in which we live, the constant ebb and flow of the news cycle and the inevitability of never fully understanding what it means to live life as a person of color, how can white adoptive parents provide a safe and validating environment for their children to cultivate and express their unique racial identity? What are some things as a transracial adoptee I would want all white adoptive parents to know as they consider this journey?

1. Diversify your bookshelves. It feels like this is so obvious, but I will never stop repeating it because I believe in its enduring power to create a positive self-esteem. Your child needs to see themselves in their bedtime stories, on the TV, in the art in your office, and in your holiday decorations.

Some of my favorite memories as a child were reading All the Colors of the Earth (https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/409344.All_the_Colors_of_the_Earth) with my mom and getting to play with the African Kwanzaa figurines at Christmas time.

At 26-years old I still have some of my favorite storybooks proudly displayed on my bookshelf and still read them with love.

-

Happy to be Nappy: https://www.amazon.com/Happy-Be-Nappy-Board-Book/dp/1484788419

-

When God Made You: https://www.amazon.com/When-Made-Matthew-Paul-Turner/dp/1601429185

-

Books by Ezra Jack Keats: https://www.amazon.com/s?k=Ezra+Jack+keats&i=stripbooks&ref=nb_sb_noss_2

-

And That’s Why She’s My Momma :https://books.google.com/books/about/And_That_s_Why_She_s_My_Mama.html?id=xr6gtAEACAAJ&source=kp_cover

2. Develop meaningful relationships with people of color. Your child needs to see you developing relationships with people of color for the value of those relationships in YOUR life, not just your child’s life. People of color should be peers, mentors, confidantes that enrich your life with friendship and leadership. Your child should know by looking at your life that people of color are important. If you are hoping to adopt, I highly recommend sitting down and brainstorming ways you can begin creating a multiracial community that can be part of your life before and after you adopt. Seek out racially and ethnically diverse places of worship. Attend activities and workshops at your local library. Check out festivals and history events. If you have already adopted but do not have black or brown relationships, it’s never too late to start. Remember, people of color are not a “diverse friend” to be checked off on a list and they aren’t your personal race consultant – be sure to value the brown and black people in your life for who they are and not what they can give you.

3. Advocate for the personal and political interests of your child’s community. It’s important for your child to see you educating yourself, sticking up for black and brown people in conversation, staying up to date with the news and policy-changes that impact communities of color. Your child should see and know that their community is now your community. The willingness you have to advocate for people of color will directly translate to your willingness to advocate for your child of color.

4. Diverse community is an intentional choice not a haphazard accessory. Field trips to the Black history museum and culture campus once a year are not going to provide your child the opportunity to explore their racial identity and learn from others about what it means to be brown or black in the world. Because I did not have friends of color until college, it was an awkward, confusing and painful experience to open up to and get to know other people of color. By living in a different neighborhood, or seeking out a more diverse place of worship, I could have begun developing relationships with people of color far before I left high school, giving me the skills and confidence to continue forging those meaningful connections. Lack of engagement with black and brown people in consistent and positive ways early in your child’s life can hinder their ability to relate to and build relationships with people of color later on.

5. It’s okay not to have all the answers. In fact, you won’t have all the right answers. While every parent wants to provide the absolute best for their children, I find white adoptive parents are especially eager to fill the gaps they fear their child might experience. It’s important to realize that even if you “check” off all the so-called right boxes in terms of providing your child an environment where they can foster a positive racial identity, your child might still struggle with their racial identity. It’s more important to focus on ways your child can cope with frustration, sadness, etc. than trying to prevent them from experiencing those emotions.

Things my parents did well:

-

They incorporated my racial identity in daily life. From books, to music, to plays to household art, my parents made sure I was able to see my racial identity reflected in our home.

-

They listened. Conversations about race can be hard and messy. Sometimes feelings are hurt, and experiences are misunderstood. My mom could have easily entered into conversations about race with an arsenal of excuses, justifications and explanations. But she didn’t. She set down her defenses and did her best to simply listen.

-

They didn’t rely on me for education. While I might suggest books or articles about race my mother always went the extra mile to roll up her sleeves and do the heavy lifting herself.

-

They take my personal safety seriously. They don’t minimize the oftentimes violent situations I might encounter living in an area of the Midwest that continues to have active hate groups. They check in, stay up to date on national news, and give me an extra financial boost for buying a better parking pass or purchasing personal self-defense devices.

-

They always celebrated by racial identity. My skin, my hair, my racial history was always spoken of with love.

-

They believed me. When I would (and still do) come home with experiences of racism or prejudice they don’t question if it’s true. They don’t ask me if I did something wrong. They don’t brush it under the rug. They don’t tell me I’m over-reacting. They trust that my experiences as a woman of color in the world are real and valid.

Living as a woman of color in an oftentimes unpredictable racial climate can be scary, exhausting and discouraging and living as the parent of a transracial adoptee in such an environment can be difficult. Just as I believe I can walk this life as a woman of color with grace and intention despite the obstacles, I believe transracial adoption, though complicated, is possible. Once hopeful adoptive parents view their child’s racial identity as worthy of just as much emotional labor as other aspects of their child’s well-being, they can begin to equip their child with the necessary tools to view the difficulties of transracial adoption not as insurmountable burdens but as enriching complexities in their already beautiful life.

Torie and her family in the hospital after she was born

Torie and her family in the hospital after she was born